The urgent need to combat climate change has accelerated efforts to electrify and decarbonize buildings, heralding a promising shift towards sustainable energy sources. As society embraces this transformative journey, it is crucial to acknowledge the potential unintended consequences of such endeavors, particularly for frontline communities and Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC). Historically marginalized and disproportionately affected by environmental disparities, these communities may face unique challenges in adopting clean energy solutions and accessing the benefits of the green transition.

Addressing these concerns requires a holistic approach that includes financial support, equitable community engagement, affordable housing protections, green workforce development, health impact assessments, and cultural sensitivity. As IMT has collaborated with community-based organizations and local governments, the following harms are frequently mentioned. When governments, utilities, and the real estate industry pursue decarbonization, they must address the unique issues within their community, which may go beyond this list.

In part two, I’ll dig into more detail with the potential solutions. Hint: community leadership is the key.

Potential Harm Caused by Building Decarbonization

Energy Cost Burden

Frontline communities and BIPOC households often have lower incomes and may already struggle with high energy costs. Electrification and decarbonization efforts could potentially lead to an initial increase in electricity costs as the transition occurs, putting a disproportionate financial burden on these communities. This affordability concern may hinder their ability to access clean energy technologies, exacerbating existing energy poverty.

Displacement and Gentrification

As urban areas undergo electrification and decarbonization, there is a risk of displacement and gentrification. As the value of properties increase due to electrification efforts, it can lead to rising property taxes and rent, making it difficult for long-standing community members to afford living in their neighborhoods. This gentrification can result in the forced relocation of vulnerable populations to areas with fewer resources and limited access to essential services.

Lack of Access to Benefits

Frontline communities and BIPOC individuals might not have equitable access to the benefits of electrification and decarbonization. For example, they may not have the financial means or administrative capacity to invest in clean energy technologies, access energy efficiency incentives, or participate in community solar programs. In the case of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), many of the tax deductions and rebates for big-ticket items like electric stoves and heat pumps are more accessible to homeowners. Renters may have to rely on landlords for upgrades that transition the building from fossil fuels. This disparity could further deepen existing social and economic inequalities.

Employment Disparities

Jobs created in the clean energy sector during electrification may not be equally accessible to frontline communities and BIPOC individuals. Barriers such as educational requirements and discriminatory hiring practices could limit their access to new green jobs, perpetuating employment disparities.

Check out our Emerald Cities Collaborative’s resources for economic inclusion.

Health Impacts

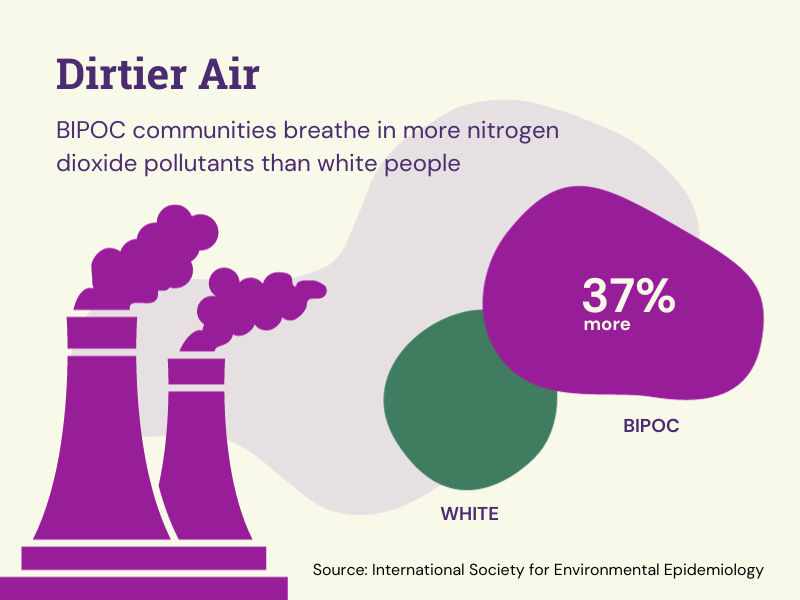

While electrification and decarbonization aim to improve overall air quality, certain communities may face temporary disruptions during the transition. Construction activities and retrofitting of buildings can release pollutants and particulate matter, impacting air quality and potentially causing health issues for those living in close proximity to these activities.

Tribal Sovereignty Limitations

Tribal nations are often not included in electrification and decarbonization efforts such as codes and regulation adoption, utility development, and financial incentives for building stock electrification. Not adding language to specifically include tribes, and not including tribes in the program/policy/regulation drafting and adoption processes both limits the ability for tribal nations to be proactive in furthering their own decarbonization goals and reactive to the policies set by the state/federal government.