Fighting climate change means taking big steps to create healthier, more resilient, and more efficient buildings while reducing harmful emissions across communities.

Understanding this, leading governments are adopting building performance standards that require building owners in their communities to improve the energy and climate performance of their properties. IMT has helped local and state governments design and implement these policies since Washington, DC first adopted its BPS in 2018. Based on our experience supporting these trailblazing communities, we have created model BPS legislation and implementation guidance.

Building Your BPS Team

IMT recommends establishing four interrelated entities to address the full scope of roles and responsibilities needed to implement a BPS.

Implementing Department

Government office responsible for implementation and management of the BPS.

Building Performance Improvement Board

Advisory board composed of experts in building science and real estate.

Technical Committee

Committee of the BPIB composed of architects and engineers with deep expertise in building science.

Performance Metrics

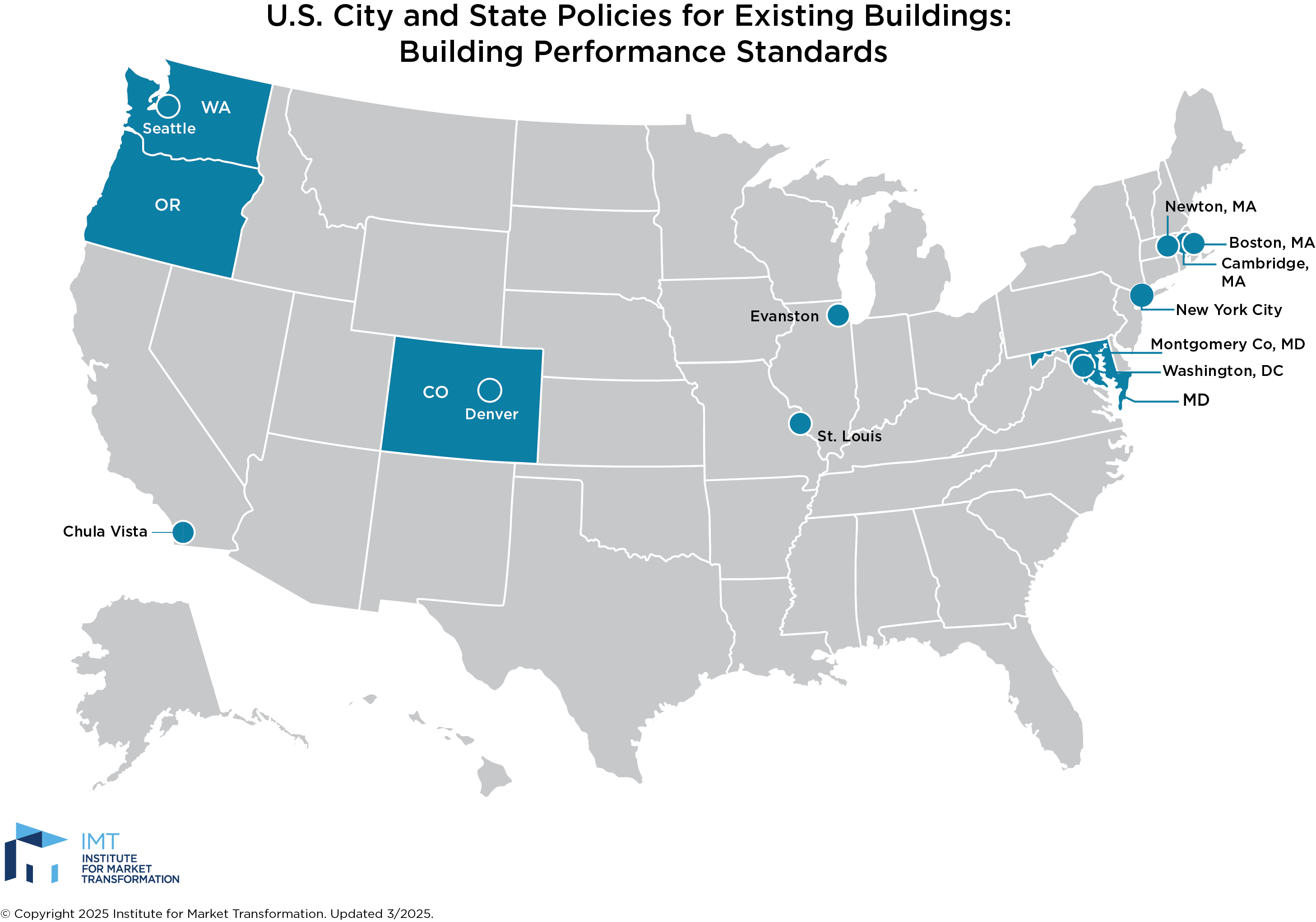

BPS policies are expanding rapidly as many jurisdictions recognize the key role buildings play in meeting climate goals and in addressing social justice. However, each jurisdiction sets performance standards in the way that makes sense for them. See our matrix for a detailed comparison.

Jurisdiction Examples

Per its BPS law, Washington, DC chose to set most of its standards for most property types at the local median ENERGY STAR score for each property type. Before drafting its law in 2018, DC applied for technical assistance to analyze the potential energy and GHG reductions for a BPS as well as the cost implications for building owners. The consultants, C40 Cities and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, used data from the DC Sustainable Energy Utility to estimate the costs and savings at the building level.

Washington used an amended version of ASHRAE Standard 100 – Energy Efficiency in Existing Buildings to set EUI targets for covered properties. Rather than estimate compliance costs for covered properties, the state wrote a requirement into its law that buildings that do not meet the standard on their own by the compliance deadline will go into a conditional compliance path. These owners will need to do an energy audit and energy management plan that uses life-cycle cost analysis to determine a bundle of measures that will meet the standard with a savings-to-investment ratio of 1.0 or greater. Thus, no owner will be required to pay for uneconomic improvements.

New York City used audit data collected under Local Law 87 to analyze the most cost-effective energy and GHG reduction strategies in its large building stock. See One City Built to Last, by the Buildings Technical Working Group, a Mayor-convened task force of more than 50 leaders in real estate, building design, construction, finance, and environmental justice, for tables estimating the cost per square foot and annual cost savings per square foot of common energy conservation measures. See Turning Data Into Action: Retrofitting Affordability, to see packages of energy conservation measures and their estimated costs that the authors developed for NYC multifamily housing buildings.

Boston hired a consulting company, Synapse Energy Economics, to recommend GHG standards for each covered property type and to estimate the cost of common emission abatement strategies. See page 25 of this report to see a description of Synapse’s methodology. The June, July, and September presentations in this folder offer detailed descriptions of the inputs Synapse used to develop and model the abatement strategies.

|

|

|

Read the Full Implementation Guide

This guide is written to correspond to the requirements of implementing a BPS recommended in IMT’s Model Law for a Building Performance Standard, which provides the structural foundation for a BPS law in any jurisdiction. Throughout this guide, you will find many references to corresponding recommendations and sections in the model law.

IMT’s Corporate Engagement Opportunities Program

Are you a building owner or service provider? Learn more about how to prepare yourself and your clients for building performance policies, avoid non compliance fees and risk from policy exposure, save time on self-education, and stay competitive in your offerings with resources from IMT’s Corporate Engagement Opportunities program.