The grid is such a normal part of our life that we often overlook the electric interstate running parallel to our own roads. The poles and wires that we see every day from our homes and highways are the part of the grid called ‘the distribution system.’ It’s the section of the grid that delivers electricity to our neighborhoods and businesses and has been described by the U.S National Academy of Engineering as the greatest engineering achievement of the 20th century.

With its ubiquitous presence, the distribution system offers a unique opportunity to implement clean energy and energy justice practices on a national scale. A demonstration of this opportunity in practice comes from work IMT did in Oregon, where we collaborated with two community-based organizations (CBOs) – Verde and the Coalition of Communities for Color (CCC) – to advance energy justice in the utilities’ distribution system plans. This work is a great example of how we can reimagine existing utility structures to better serve the priorities of the people.

Shining a Light on Grid Injustices

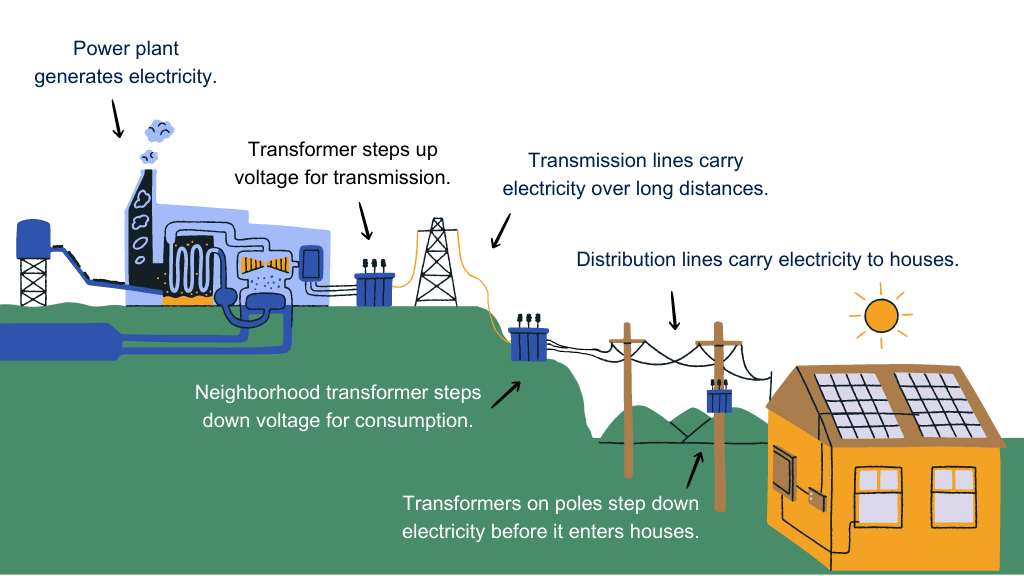

The distribution system starts at a substation, which takes high voltage electricity delivered from power plants via transmission lines, and steps the electricity down to a low voltage that our outlets can use. Then that lower voltage electricity is delivered to the end users – our homes and businesses – via the distribution lines that we’re accustomed to seeing along our streets and alleyways.

The distribution grid plays a key role in where, when, how quickly, and at what cost distributed energy resources (DER) like rooftop solar or building electrification are deployed. This is determined by the capacity of the distribution infrastructure that those DERs are interconnecting to. The distribution grid is split up into subsections called feeders or circuits, and each circuit is built to be able to handle a certain amount of electrical load. If this threshold is exceeded, the utility and/or DER installer will have to invest a potentially significant amount of money to upgrade the grid infrastructure.

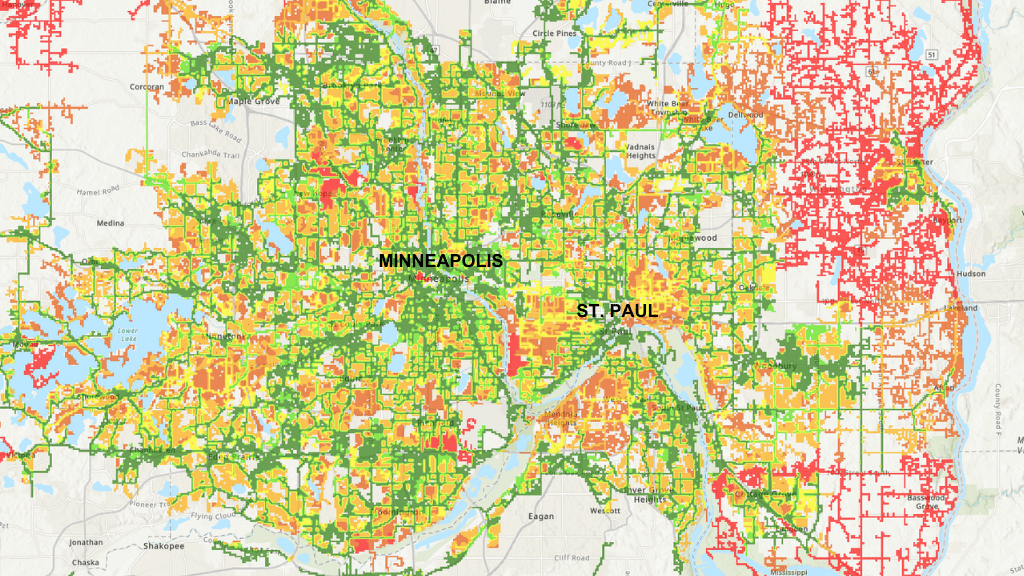

However, only the utility knows when this threshold will be crossed until they start a project. In order to increase transparency, some jurisdictions, through their utility regulatory bodies – the public utility commissions (PUC) – are requiring utilities to report hosting capacity, or the amount available on each feeder to host new load. As an example, the map below shows Xcel Energy’s Hosting Capacity Map for the greater Minneapolis area, where IMT has worked for a number of years. The green feeders have room to host more resources while the red areas do not, and will require upgrades. Maps like this, and the underlying data, can help developers and energy justice advocates understand the geographical distribution of grid limits.

Historically disadvantaged communities often have more inefficient buildings and less access to clean energy technology. This means that the higher energy load from buildings in disinvested neighborhoods can stress the local grid more than other areas, likely leading to a higher instance of grid constraints in underserved communities.

A recent paper “Inequitable access to distributed energy resources due to grid infrastructure limits in California” explored the unsurprising connection between hosting capacity and discrimination. The authors layered publicly accessible hosting capacity data in California over a variety of population data and equity metrics to investigate if grid constraints affect demographic groups differently. The authors found that “grid limits exacerbate existing inequities: households in increasingly Black-identifying and disadvantaged census block groups have disproportionately less access to new solar photovoltaic capacity based on circuit hosting capacity.” As a first of its kind analysis, any jurisdiction with public hosting capacity data can replicate this to find out how their distribution system helps or exacerbates existing inequalities.

Oregon’s Endeavor for Equitable Distribution Planning

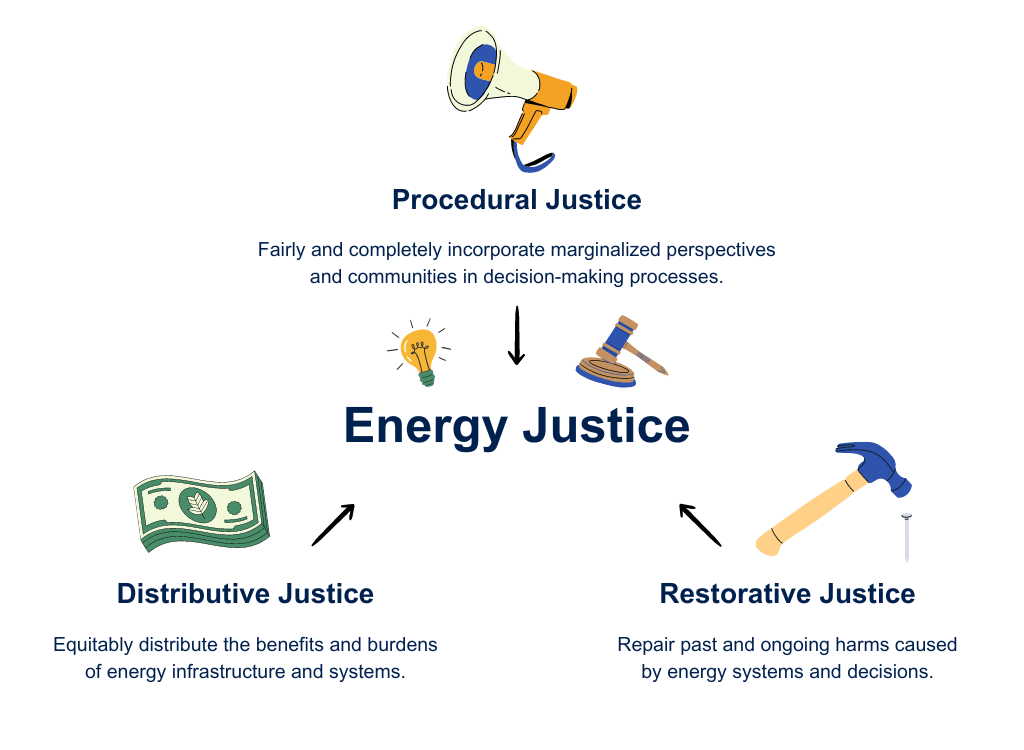

In December 2020, Oregon joined a growing list of 26 states that are either investigating, implementing, or have established some form of enhanced Distribution System Planning (DSP or Integrated Distribution Planning) practices. This approach invites stakeholders, including CBOs, to provide input on how the state’s utilities should plan and invest in their distribution system. Historically CBOs have not had a seat at their utility’s decision-making table, but recent years have seen an uptick in participation as more climate and environmental justice groups identify public utility commissions as key forums for energy policymaking, and have devoted some of their limited time and resources to participate. At the same time, some PUC are making efforts to improve procedural equity in their processes by expanding intervenor compensation programs and providing more opportunities for public participation.

Driving Community Wealth with Utility Investments

IMT had the opportunity to support two local organizations who were already deeply engaged in the DSP – Verde and the Coalition of Communities of Color (CCC). Together, we submitted formal comments and worked directly with Portland General Electric (PGE) and Pacific Power (PAC) to blaze a new trail for equitable distribution planning. The overall goal of our collaboration was to redirect as much as possible of each utility’s annual spending on its distribution system ($350 million for PGE and $170 million for PAC) to investments that simultaneously solve grid constraints and build wealth in underserved communities.

At a high level, our comments suggested the utilities:

- Engage their community members in a meaningful, non-technical manner and provide a record of how their input was incorporated as technical changes to the DSP.

- Map energy burden, demographic, and other equity data onto the hosting capacity map so that stakeholders can connect grid constraints with other relevant human conditions.

- Develop a ‘community benefits test’ to examine the value of proposed utility investments to the communities the utilities serve and prioritize investments that deliver the most benefit to communities.

- Propose non-wires solutions — or strategies like solar, storage, efficiency improvements and other DERs that solve grid inefficiencies without relying on costly distribution system infrastructure upgrades — that are intentionally designed to maximize co-benefits like building wealth and resilience in underserved communities.

In their full plans filed in August 2022, both PGE and PAC took up some of our recommendations, including:

- PGE hosted a series of community-focused workshops to encourage the inclusion of energy justice advocates in the DSP conversations and included the key takeaways as well as plans for continued engagement in the next planning cycle in their filing.

- PGE acquired the Greenlink Equity Map to overlay energy burden data onto their hosting capacity/Distributed Generation Evaluation map.

- PGE is working to develop a non-wires solution selection and analysis process that incorporates equity factors.

- Both PGE and PAC are required to propose two projects in the August filing that “address community needs”.

- PAC has created a Community Input Group to solicit feedback on their plan and process.

- Conversations are underway to either create a community benefits test or incorporate the underlying ideas in other benefit-cost analysis methods.

As more governments, utilities, regulators, and CBOs work together to advance energy justice, the progress in Oregon provides a powerful learning opportunity. It serves as a model for human-centered distribution system design and planning, where the utility engages deeply with impacted organizations to co-develop solutions that provide direct community benefits. The utilities in Oregon have demonstrated through this process a commitment to community engagement that is based on the belief that those impacted by a decision, program, project or system need to be involved in the decision-making process. We hope to see and advocate for this level of engagement in the utility planning process in other jurisdictions. For more information on this project, or opportunities to engage in your utility’s distribution system plan, reach out to Julia Eagles.