On a sweltering afternoon in July, in the City of New Orleans Council chambers, something quietly transformative happened: the City Council voted unanimously 7-0 to adopt Ordinance No. 35,154 to amend Chapter 26 of the Code of the City of New Orleans a.k.a. the Building Energy Benchmarking Ordinance.

This new law requires owners of non-residential and multifamily properties over 20,000 square feet to measure and publicly disclose their annual energy use to the City. For the people in the room, the vote was over in minutes. But for those who had spent years organizing, researching, advising, drafting, testifying, dealing with setbacks, and pushing this policy forward, this moment was a long time coming.

The long road to a simple idea

The premise of benchmarking is simple: track how much energy large buildings use, report that data publicly, and give owners, tenants, and the public a window into performance. The act of simply recording and sharing this data can have big consequences.

On average, buildings that benchmark reduce their energy use by 2.4% each year. Benchmarking data from NYC shows a 26% reduction in emissions from buildings between 2010 – 2023, and that there was a 10% reduction of site energy use intensity in the city’s mid-sized buildings (buildings between 25,000 and 50,000 square feet) after the benchmarking law was expanded to include them in 2016.

More importantly, benchmarking lays the groundwork for broader reforms, like offering targeted incentives to improve energy efficiency, or setting building performance standards, which is crucial for New Orleans where 20% of the City’s greenhouse gas emissions come from energy use in large buildings alone.

But, in New Orleans, turning that simple idea into law took over a decade.

City staff have been involved in local benchmarking efforts since 2014 when the City began benchmarking its own municipal buildings. Between 2018 and 2021, that effort helped reduce energy use by 23%, demonstrating the power of data-driven energy management. New Orleans also became a member of the City Energy Project, and as part of this effort they created a baseline of existing energy use in municipal buildings that allowed them to identify the most beneficial energy efficiency upgrades across their portfolio. This was also the beginning of developing a proposed benchmarking ordinance that would cover privately-owned buildings.

Staff at the City’s Office of Resilience and Sustainability (ORS) were deeply involved in these efforts for years, although original benchmarking efforts began in the City’s Chief Administrative Office, and have acted as the main drivers of the policy. Over time, ORS advanced the policy by meeting with private sector stakeholders, explaining the ordinance’s intent, responding to concerns, and outlining the benefits and cost savings benchmarking can unlock.

Unfortunately, their efforts continued to face headwinds, and it wasn’t until some four years later that momentum began to build.

In 2018 and 2019, the New Orleans City Council, led by Council Vice President Helena Moreno, started to lay the groundwork for benchmarking by passing a series of resolutions directing their utility, Entergy New Orleans (ENO), to provide aggregated energy data to multi-tenant buildings. This compelled ENO to develop its aggregated usage data tool and set the stage for citywide benchmarking. The next year, the City of New Orleans joined the National Building Performance Standards Coalition—publicly committing to building performance policies.

Local leadership was matched with federal momentum. In July 2024, the City secured nearly $50 million in EPA Climate Pollution Reduction Grant (CPRG) funding—including over $1.5 million dedicated specifically to launching a citywide benchmarking program. That money is now ready to be put to work, even as the federal government has eviscerated support for climate action.

In June 2025, the City publicly launched its Municipal Building Energy Use Dashboard, making that data accessible to the public for the first time. The dashboard tracks metrics like Site Energy Use Intensity, greenhouse gas emissions, and ENERGY STAR scores (if available) across City-owned facilities, reinforcing the necessary transparency and accountability at the core of the new ordinance.

The coalition behind the final stretch

While the City’s most recent Climate Action Plan set the goal of passing an ordinance in 2024, by Spring 2025, language for the ordinance hadn’t been introduced in committee. With City elections looming in the fall and uncertainty about what a new council and mayor might prioritize, time was running out.

A coalition of supporters kept the conversation moving and the policy progressing forward. Public Health Law Center (PHLC) provided legal technical support throughout the process. IMT provided technical advice, national context, and policy drafting support. And the Alliance for Affordable Energy (AAE), a respected local utility watchdog, contributed their local expertise and activated its network of community partners to build awareness, trust, and momentum.

Ultimately, this work was successful. After much debate, the draft ordinance was officially introduced to the public in June 2025 at a joint City Council committee meeting, where members voted unanimously to advance it even before it had been formally introduced. It was officially introduced for first reading on June 26, and at the next Council meeting on July 10, it passed unanimously.

What the ordinance requires

The new law requires owners of non-residential and multifamily buildings over 50,000 square feet to track and report their annual energy use beginning in 2026. Buildings between 20,000 and 49,999 square feet are phased in by 2027. The data will be reported via EPA’s ENERGY STAR Portfolio Manager—a free federal tool that is the gold standard for building energy tracking.

Building owners must make “reasonable efforts” to collect whole-building data, even from tenants in multi-tenant buildings, though exemptions exist for hardship or unique industrial uses. After a one-year grace period, the first violation carries a fine of $1000 with subsequent fines of $60 per day. The combined penalty amount is capped at $3,000.

What it means for New Orleans

“Getting a benchmarking law over the finish line may not seem flashy. But it’s a fundamental tool a city can use to shine light on how our buildings work—and who benefits.”

Logan Atkinson Burke, Executive Director of AAE

There is a tendency to focus only on what ordinances require, but what they make possible is equally (if not more) important. For the first time, the City and its residents will have visibility into the energy performance—and associated climate impact—of the large buildings where they live, work, and play (🎊laissez les bons temps rouler!⚜️). With access to information about the energy they are using, tenants can better understand and forecast their utility bills and building owners are more likely to prioritize energy efficiency improvements.

This connection is especially significant in New Orleans because the City Council serves as the regulator for ENO—a rare arrangement that gives the Council direct authority over the city’s investor-owned utility. Benchmarking data gives the Council a stronger basis to align utility planning, energy incentives, and grid reliability investments with the needs of residents and businesses. That’s significant in a city and region that struggles with repeated grid reliability crises, including a forced blackout during Memorial Day weekend earlier this year.

A foundation, not a finish line

For all its significance, this ordinance is just the beginning. Benchmarking is a data tool, not a final product. But it’s a tool that catalyzes less energy waste and better economic outcomes for residents and businesses, and this accelerates progress toward climate and environmental justice. The persistence, partnership, and shared purpose of this group will help maintain momentum beyond this single success, allowing New Orleans residents to fully benefit from this first step.

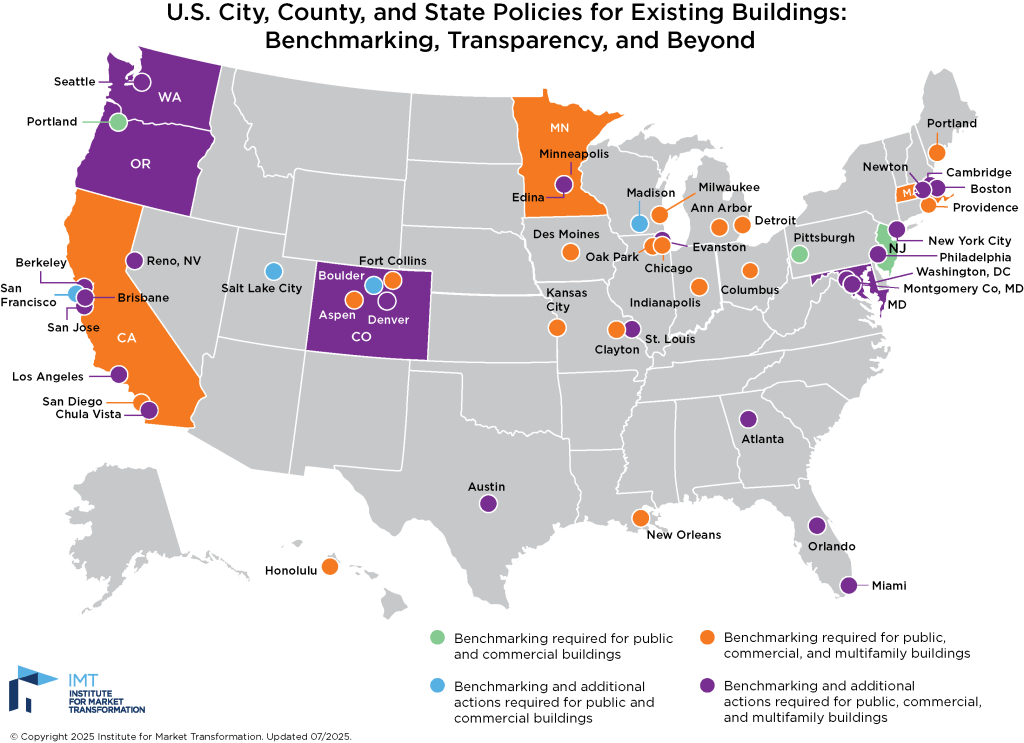

To dig into where benchmarking is being adopted across the country, check out IMT’s Maps and Comparison resources.