The code development process for the 2024 International Energy Conservation Code (IECC) is currently underway, and the cost-effectiveness of efficient code is again being questioned. Opponents to higher efficiency code argue that energy efficiency requirements in code will increase the cost of homes, which will further worsen the affordable housing crisis as homebuyers are priced out. The National Association of Home Builders commissioned an analysis (performed by Home Innovations Research Lab) of the 2021 IECC that claims that the new code is not cost-effective, and therefore a bad deal for consumers. So…is it?

Well, no. This narrow perspective doesn’t take essential concepts into consideration and prioritizes lowest initial cost to build above everything else, including longer-term affordability. Seem contradictory? Stick with me.

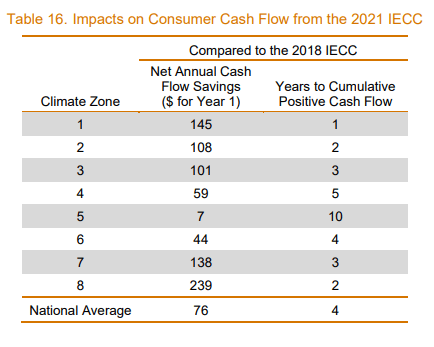

Part of the issue is disagreement on the best means to calculate cost-effectiveness. While appliances and HVAC equipment last approximately 10 to 20 years, other components such as the building envelope can last the lifetime of the building, which means the value of efficiency features should be evaluated over 30 to 40-year timeframes. While efficiency improvements in energy codes may increase the initial purchase price of a home, it is only by a small amount, and may soon be offset by utility bill savings. This is best demonstrated using either the life-cycle cost (LCC) approach or cash flow analysis, rather than simple payback. LCC considers the full costs and benefits over the life of the building, while mortgage cash flow analysis captures the most realistic perspective of the effect of energy codes on a typical homebuyer by calculating year-by-year annual net cash flow (see the Methodological Comparison of Cost Effectivness). Since the vast majority – 87% – of homebuyers finance their purchase, these additional costs in purchase price are distributed over a long period of time, meaning that increased code stringency doesn’t cause much of an increase in the initial cash required for a home purchase.

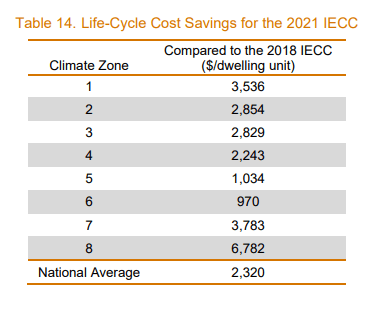

In fact, energy efficiency measures are not the primary driver that keeps buyers out of new homes. More significant factors are low inventory that increases valuations, low credit scores caused by inaccurate reporting, income bias and a variety of larger social challenges, and, per NAHB, rising interest rates. While the 2021 IECC raised construction costs by $2,372 compared to the 2018 IECC, that accounts for only 0.6% of the average cost ($391,900) of a new home in 2021. In 2020, the median household income for the U.S. was $67,521 compared to the average new construction homebuyer who had a household income of at least $100,000. Those most concerned with housing affordability are, instead, likely to look to existing homes, which still price out most buyers at an average of $334,500. In fact, in 2020 more than half of U.S. households were unable to afford even a $250,000 home. The benefit of constructing new homes with efficiency measures already built-in means the improvements are available for the next owner, perpetuating energy and cost savings for the life of the building. While the cost associated with the higher efficiency levels in the 2021 code does increase initial investment, these measures remain cost-effective with an average of four years to cumulative positive cash flow for all climate zones. This results in decades-worth of affordable utility bills, comfort, and health benefits for the people living in these homes.

So why is there resistance to consistently improving the efficiency of the code each cycle? Businesses naturally try to minimize risk and cost, and it costs more to evolve supply chain strategies and retrain employees in the latest building code updates. This bolsters the argument in favor of developing a long-term glide path for efficiency in building codes. This would provide insight into future training and planning needs for builders, and give building component industries an indicator of long-term supply needs, motivating innovation and an infusion of investments in these sectors. To provide additional clarity and consistency, the most recent energy code should be uniformly adopted in every jurisdiction, but we’ll save that conversation for another day. Today, 2024 IECC committee members should continue to prioritize cost-effective incremental efficiency improvements in the code as a means to support housing affordability, not just for today, but for decades into the future.