This fall, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and Fannie Mae achieved a major milestone by launching the first ever ENERGY STAR® score for multifamily housing—a mix of apartment buildings, condominiums, and other units that have become a staple of America’s built environment.

This is noteworthy because up until now, the lack of an ENERGY STAR 1-to-100 energy-performance score for multifamily buildings (with the exception of newly-constructed high rises) has had a negative impact on the value of energy benchmarking and transparency laws—which are providing foundations for successful energy efficiency strategies in a growing number of U.S. jurisdictions— including 10 cities, two states, and one county. Multifamily buildings represent a significant portion of building stock in these affected areas and the lack of a comparable metric to benchmark this property type has created a blind spot in the larger benchmarking policy picture.

To address this, Fannie Mae’s Multifamily Energy and Water Market Research Survey provided the EPA with crucial energy data, allowing the agency to develop a data baseline for multifamily buildings (similar to what the U.S. Department of Energy’s Commercial Building Energy Consumption Survey —CBECS— provides for commercial buildings). With a baseline established, properties with 20 or more residential units can now receive a ENERGY STAR score of 1 to 100, providing occupants and owners with greater insight into how their buildings are using (and potentially wasting) energy and how they compare to their peers. And with this new score, Fannie Mae is able to link the energy and financial performance of multifamily buildings nationally for the first time.

Owners and operators can enter the required building characteristics and utility information into EPA’s Portfolio Manager®, a simple and free web tool that 40 percent of U.S. commercial buildings are already using to measure and track their energy use. Properties that score a 75 or above can pursue ENERGY STAR certification to receive the coveted ENERGY STAR plaque to market energy-saving achievements to both investors and potential tenants.

Owners and operators can enter the required building characteristics and utility information into EPA’s Portfolio Manager®, a simple and free web tool that 40 percent of U.S. commercial buildings are already using to measure and track their energy use. Properties that score a 75 or above can pursue ENERGY STAR certification to receive the coveted ENERGY STAR plaque to market energy-saving achievements to both investors and potential tenants.

For the six cities that already have ENERGY STAR benchmarking requirements for multifamily buildings, Fannie Mae now requires any property with a Fannie Mae Multifamily loan to report its score, which gives Fannie Mae the ability to do long-term tracking of these buildings’ ENERGY STAR scores and financial performance.

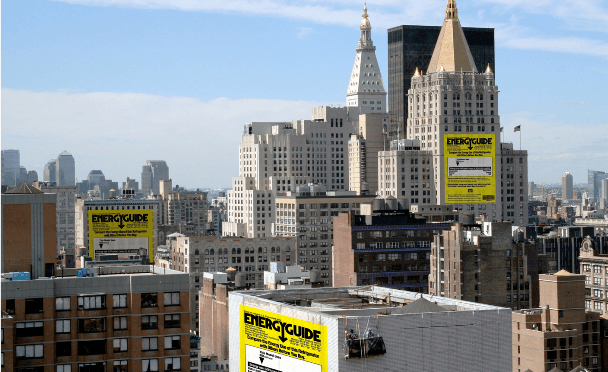

This is another step in the right direction for energy transparency in the multifamily sector, and one that brings energy use into better focus for its many stakeholders. As the old adage goes, you can’t manage what you don’t measure, and consumer-friendly metrics matter—particularly for residential renters—so it’s important that energy-performance data transparency is straightforward and compelling, much like miles-per-gallon stickers on vehicles and nutritional labels on food.

This is another step in the right direction for energy transparency in the multifamily sector, and one that brings energy use into better focus for its many stakeholders. As the old adage goes, you can’t manage what you don’t measure, and consumer-friendly metrics matter—particularly for residential renters—so it’s important that energy-performance data transparency is straightforward and compelling, much like miles-per-gallon stickers on vehicles and nutritional labels on food.

However, given the new eligibility for multifamily buildings to receive ENERGY STAR certification, and the increasing awareness of how beneficial benchmarking can be, will a stampede of the sector’s building owners and operators be racing to enter and track their energy usage in Portfolio Manager? Maybe not, as data access, regulatory, and privacy issues persist. Even though any property can use the Portfolio Manager program, ENERGY STAR ratings are only available for properties that can record aggregated, total energy consumption. As a result, buildings in locations where utilities don’t offer whole-building consumption data are simply ineligible for scoring.

There has been some recent movement on better data access, with the National Association of State Utility Consumer Advocates (NASUCA) unanimously passing a resolution last year that supports multifamily building owners getting access to whole-building energy data, as long as the privacy of tenants is protected. Partners of the U.S. Department of Energy’s Better Buildings Energy Data Accelerator have also committed to put systems in place to provide whole building data to at least 20 percent of its commercial and/or multifamily building owners by the end of 2015.

In addition to these initiatives, a more sustained and large-scale effort is needed for better data access, as we see aggregated, whole-building energy data is crucial not only to be eligible for an ENERGY STAR rating, but also for building owners to be able to evaluate and justify energy efficiency upgrades and to track performance. In the meantime, property managers should lobby for better access and take other actions such as revising lease clauses to require occupants to share utility data with them—many of this year’s Green Lease Leaders achieved this with their tenants.

Despite the hurdles that exist, the 1-to-100 ENERGY STAR score for multifamily housing is a significant development for America’s built environment and one that can help shine a brighter spotlight on energy use in the sector. Millions of Americans, including three out of every four renters and a significant share of minority and lower income populations, now live in multifamily housing. The population residing in these properties has swelled in recent years, as more people have opted out of homeownership since the financial collapse—due to unemployment, slow wage growth, and difficulty obtaining a mortgage, among other reasons.

With so many of us now living in multifamily properties—which have a median age of 36 years, most of which were constructed before modern building energy codes were adopted—the potential for money and energy savings is vast, and greater transparency in the marketplace that ENERGY STAR scores provide can help tap into it.